On November evenings when stadiums across India should have been heaving under floodlights, Indian football’s biggest showpiece — the ISL — is missing from the calendar.

No opening ceremony. No new kits. No “Let’s Football”.

This was supposed to be a season of countdowns. New foreigners landing at airports, teaser videos from clubs, fans blocking Sundays for double-headers. Instead, the 2025–26 Indian Super League exists only as a rumour and a row in court documents. The country’s top league has been officially put “on hold”, with no confirmed start date and a very real chance that it may not happen at all.

At the centre of it all is a contract written 15 years ago, a Supreme Court order, and a power struggle over who really runs Indian football. Around that centre are hundreds of players – from national icons to fringe squad members – watching their contracts freeze, disappear or get rewritten on the fly.

Legal tangle that kicked off woes

The roots of this non-season run back to 2010, when the All India Football Federation (AIFF) signed a long-term Master Rights Agreement (MRA) with IMG–Reliance, whose role later passed to Football Sports Development Limited (FSDL), the Reliance-led company that created and operates the ISL. That deal handed FSDL sweeping commercial rights: broadcast, sponsorship, league operations.

For a decade the arrangement held, even as critics complained that the federation had outsourced too much control to a private partner. But by mid-2025, the MRA was nearing expiry, FSDL wanted clarity on the future, and AIFF was itself under Supreme Court scrutiny over its governance and compliance with India’s sports code.

In April, a key twist happened: as part of an ongoing case around AIFF’s new constitution, the Supreme Court effectively told the federation not to sign fresh long-term commercial deals until the matter was settled.

That ruling turned the MRA renewal into a legal grenade. FSDL, unwilling to run an expensive national league without a secure contract, wrote to AIFF and the clubs in July to say it was “not in a position to proceed with the 2025–26 ISL season” and was placing it on hold.

AIFF responded with reassurances and committees; the clubs responded with alarm. In August, 11 of them warned the federation – and, through it, the Supreme Court – that if the impasse wasn’t resolved, the ISL season might not be played at all and the entire professional pyramid, including the I-League, youth and women’s competitions, was at risk of shutdown.

By November, the central government had stepped in, telling the Supreme Court it would help ensure the season is held after a tender for new commercial and media rights failed to attract a single valid bid. On paper, it’s a battle about contracts, tenders and governance clauses. On the ground, it looks like this: players with no fixtures, clubs shutting training, salaries on hold, and careers drifting in the gap between two signatures.

Players caught in crossfire

One of the first clear tremors came from Bhubaneswar.

On 2 August, Odisha FC informed players and staff that all their contracts would be placed under suspension from 5 August, invoking “force majeure” – extraordinary circumstances beyond the club’s control. The reason was bluntly stated in the letter: the ISL 2025–26 season had been indefinitely suspended because AIFF and FSDL had failed to agree on a renewed MRA, and the club had no clarity on when, or whether, the league would start.

For Odisha’s captain and defensive leader Carlos Delgado, that meant going from anchoring a side in continental competition to seeing his employment effectively frozen. Delgado has been a central figure at the club since re-joining in 2022, wearing the armband and featuring regularly through the 2024–25 campaign.

Overnight, his contract – and those of teammates like Narender Gahlot, Mourtada Fall and Roy Krishna, all listed as part of the 2024–25 squad – moved into a kind of legal deep-freeze: technically still existing, but with duties and payments suspended and the club openly encouraging players to seek opportunities elsewhere or discuss mutual termination.

For an ageing foreign professional, the calculus is brutal: wait in India on a suspended deal that may or may not revive, or rip up the contract and try to find a club mid-window somewhere else in the world.

Further down the coast, the crisis touched the biggest name in Indian football. On 4–5 August, Bengaluru FC announced that it was suspending salaries for its entire first team and support staff, explicitly including veteran striker and former India captain Sunil Chhetri, citing uncertainty over the ISL season. Youth and grassroots programmes would continue, the club stressed, but top-level wages were being frozen “indefinitely”.

Chhetri is not a player living hand-to-mouth. In pure financial terms, he will be fine. But the symbolism is devastating: when the face of Indian football can have his club pay packet switched off because the league might not exist, what does that say about everyone else?

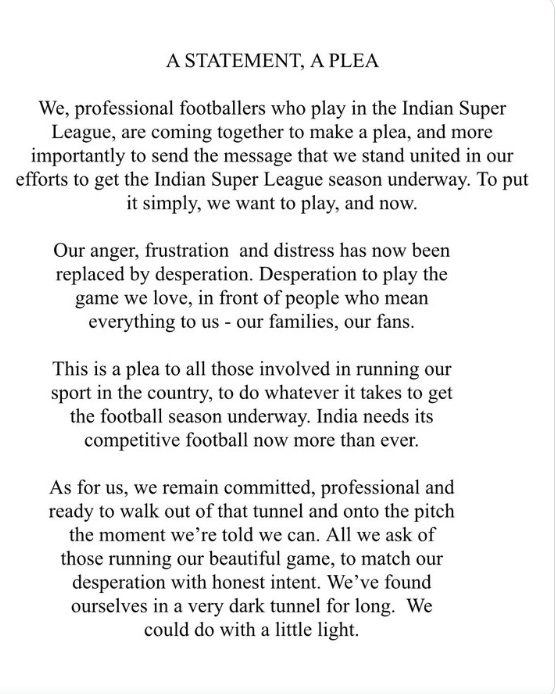

Reports around the same time spoke of “close to 400 top-tier footballers with hefty salaries” who would be directly hit if the league did not go ahead. The international players’ union FIFPRO accused some clubs of “unilateral and unlawful suspensions” of contracts and asked FIFA and the AFC to step in, warning that livelihoods, careers and mental health were at risk.

Behind each contract line is a life. One widely-reported example describes a 23-year-old ISL midfielder, unnamed for privacy, whose father is paralysed and needs constant medical care; with his club pausing salaries, the player has had to go into debt to pay hospital bills. At the other end of the spectrum are foreign stars whose Indian chapter has ended sooner than planned.

In Kochi, Jesús Jiménez thought he had finally found stability. The Spanish striker arrived at Kerala Blasters in 2024 on a two-year deal, and quickly became the club’s headline act – top scorer with 11 goals in 18 league games, the kind of centre-forward around whom marketing campaigns are built.

Then came the summer of uncertainty.

Facing a 2025–26 ISL season that might not start for months, and under pressure to plan for a “worst-case scenario”, Kerala Blasters informed their foreign players of the situation. Within weeks, the club and Jiménez mutually agreed to terminate his contract. He left on a free transfer in July 2025 and signed for Polish side Bruk-Bet Termalica Nieciecza to ensure regular football.

Here, “lost contract” isn’t a euphemism – it’s literal. Jiménez walked away from what should have been his second season in India, not because of form or fallout, but because the league that justified his move might not exist in time to keep his career moving forward.

Kerala, for their part, trimmed more first-team contracts and sent players like Ishan Pandita and Bryce Miranda out as free agents or to lower-tier Indian clubs, all while bracing for the possibility of a blank ISL calendar.

Multiply that by the league’s foreign contingent: Brazilians, Spaniards, Africans who committed to a project and a country on the assumption of a stable, televised league, only to find themselves re-entering a crowded global market with “season on hold” as the explanation for their exit.

Future of football in India remains bleak

If the crisis were just about a few clubs tightening belts, it would still be painful. But this is deeper.

Several ISL teams have halted or scaled back first-team operations. Chennaiyin FC have paused senior activities; Kerala Blasters and others have let foreign players and coaches return home; training camps across the league have been delayed or cancelled.

Across multiple stories, a common pattern emerges:

Clubs invoking force majeure to suspend all player and staff contracts (Odisha FC, most starkly). Others freezing salaries for first-team squads (Bengaluru FC, confirmed in official statements and mainstream coverage). A third group quietly letting high-earning foreigners go, mutually terminating deals or releasing them on free transfers, as with Jiménez at Kerala.

FIFPRO’s language has been unusually sharp, calling some of these suspensions “unlawful” and urging governing bodies to enforce players’ labour rights.

Meanwhile, club owners argue they have little choice. With no schedule, no broadcast income and sponsors reluctant to commit to a league that officially doesn’t have dates, the top tier’s business model has effectively stalled. What makes this all feel particularly bitter for players is that none of it is about what happens between the white lines.

They are not being benched for poor form or sold to make room for a new signing. Their ordeal exists in the pages of court petitions and tender documents: a Supreme Court that doesn’t want AIFF signing long, opaque commercial deals; a federation that insists its hands are tied; an operator that won’t risk running a league without contractual clarity; a government now trying to patch the hole with assurances to the Court that, somehow, the show will go on.

For professionals, the details blur into one hard question: Is there a league this year?

If the answer is no, the impact will echo for years. Younger players lose critical development time; veterans may quietly retire; foreign recruitment becomes harder; broadcasters and sponsors, once burned, hesitate next time. Even if the ISL is eventually rescued in a shortened format later this season, the message sent by this winter of non-football will linger.

For now, the scoreboard reads like this: contracts suspended, salaries frozen, careers diverted. The season that was supposed to begin never did, and Indian football’s most prominent league is being decided not by goals and points, but by clauses and court orders.

The only thing everyone – AIFF, FSDL, government, clubs, players – seems to agree on is that the current situation is unsustainable. But until an actual schedule appears and the ball is rolling again, the story of the 2025–26 ISL will remain one of absence: a league missing from the calendar, and a generation of professionals left wondering how a game they do on the pitch ended up being taken away from them in conference rooms.