With tensions rising between India and Pakistan, two landmark treaties have been put on the line of fire by both countries. While India has put the Indus Water Treaty in abeyance, Pakistan has retailed by banning its air space and nullifying the Simla Agreement signed between the two countries after the Bangladesh war.

Let’s take a look at what is exactly at stake here:

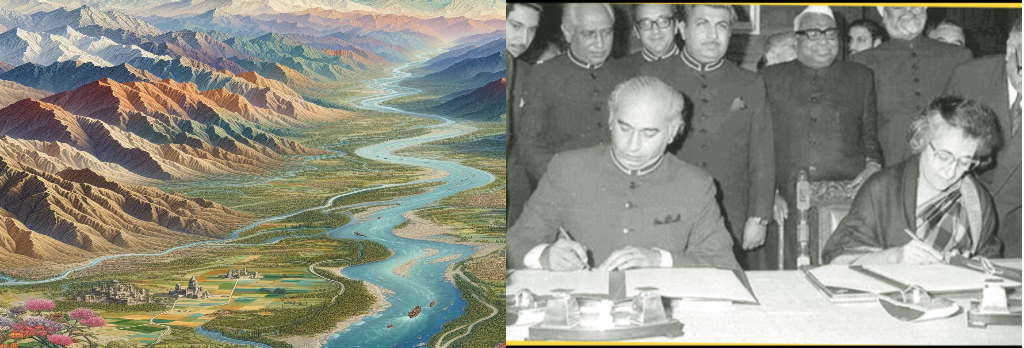

The Indus Waters Treaty: A blueprint for cooperation amidst rivalry

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) between India and Pakistan stands as one of the most enduring and successful examples of water-sharing agreements in modern international relations. Signed in 1960 under the aegis of the World Bank, the treaty managed to withstand the turbulence of wars, political tensions, and ongoing hostilities between the two South Asian neighbors. Its resilience underscores the critical role that resource sharing and structured diplomacy can play in mitigating conflict.

Following the partition of British India in 1947, India and Pakistan emerged as two sovereign states. The partition did not clearly define the control over the Indus river system, even though the rivers originating from India flowed into Pakistan. This ambiguity quickly led to disputes. In 1948, India temporarily halted the flow of water to Pakistan from the canals of the Sutlej River, leading to an acute agricultural crisis in Pakistan’s Punjab province. This early confrontation made it clear that a long-term solution was necessary to manage the shared waters.

In 1951, David Lilienthal, an American engineer and former head of the Tennessee Valley Authority, proposed the idea of an agreement. His suggestion caught the attention of the World Bank, which then stepped in to mediate between India and Pakistan. After almost a decade of negotiations, the Indus Waters Treaty was finally signed on September 19, 1960, by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Pakistani President Ayub Khan, and World Bank President W.A.B. Iliff.

Key Provisions of the Treaty

The Indus system comprises six rivers: the Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej. The treaty allocated the rivers as follows:

Western Rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab): Allocated largely to Pakistan.

Eastern Rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej): Allocated to India.

Under the treaty, India received rights to the waters of the eastern rivers for its own use, while Pakistan received rights over the western rivers. However, India was permitted limited use of the western rivers for non-consumptive needs such as irrigation, navigation, and hydroelectric power generation, provided it did not alter the natural flow significantly.

The treaty also outlined a framework for cooperation, including:

Establishment of the Permanent Indus Commission to resolve issues and facilitate data exchange.

Provisions for dispute resolution through neutral experts or arbitration under international auspices if needed.

A transitional arrangement under which India funded the construction of replacement canals in Pakistan to compensate for the loss of eastern river waters.

Significance of the Treaty

The Indus Waters Treaty is often cited as a rare example of sustained cooperation between two adversaries. Its significance can be understood in several ways:

Durability: Despite the Indo-Pakistani wars of 1965, 1971, and 1999, and numerous other skirmishes, the treaty has largely remained intact.

Water Security: It has provided a sense of stability and predictability regarding water resources, vital for agriculture and livelihoods, especially in Pakistan where about 90% of agriculture depends on irrigation.

Model for Conflict Resolution: The treaty has been seen as a model for peaceful negotiation and conflict resolution in international river disputes elsewhere in the world.

While the treaty has been remarkably resilient, it has not been without criticism and challenges:

Pakistan’s Concerns: Pakistan often accuses India of violating the spirit of the treaty by building dams and hydroelectric projects, such as the Baglihar Dam and Kishanganga Project, on the western rivers. Although India asserts these projects comply with treaty provisions, disputes have led to international arbitration.

India’s Perspective: Some Indian policymakers and commentators argue that the treaty is overly generous to Pakistan, restricting India’s use of its own resources, especially given the rising water needs of northern Indian states.

Climate Change and Population Growth: Increased demands due to growing populations and the unpredictability introduced by climate change have added new pressures to the water-sharing arrangement.

In recent years, the treaty has come under renewed scrutiny, particularly after terrorist attacks attributed to Pakistan-based groups, such as the 2016 Uri attack. Following such incidents, Indian officials publicly discussed reviewing the treaty and exploring options to maximize India’s usage of the western rivers within the treaty framework.

In 2023, India officially notified Pakistan that it sought to modify the treaty, citing Pakistan’s frequent objections to Indian projects and its refusal to resolve disputes amicably. As of now, the Indian government has put the treaty in abeyance and Pakistan has claimed that stopping the flow of water as per the Indus Treaty would be considered an ‘act of war’

The Simla Agreement: A joint pledge for bilateral peace

The Simla Agreement, signed on July 2, 1972, is a landmark accord between India and Pakistan that sought to lay the foundation for peaceful relations after the devastating Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. Beyond ending hostilities, the agreement aimed to create a framework for future engagement, emphasizing bilateralism, respect for each other’s sovereignty, and peaceful resolution of disputes. Though tested by recurring tensions and conflicts, the Simla Agreement continues to influence the dynamics between the two nations even today.

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was a defining moment in South Asian history. It resulted in the secession of East Pakistan and the birth of the new nation of Bangladesh. Pakistan’s military defeat was overwhelming: it lost a large portion of its army (about 93,000 prisoners of war), significant territory in West Pakistan (temporarily occupied by Indian forces), and, most devastatingly, its eastern wing.

Following the war, there was an urgent need to formalize a ceasefire, repatriate prisoners of war, and chart a way forward for peace and normalization. To achieve these goals, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Pakistani President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto agreed to meet at the hill town of Simla (Shimla), in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh.

Key Provisions of the Simla Agreement

The Simla Agreement is a relatively short document, but its significance is profound. Its principal elements include:

Mutual Commitment to Peaceful Resolution:

Both countries agreed to resolve their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations without resorting to arms or third-party mediation.

Respect for the Line of Control (LoC):

The ceasefire line, drawn after the 1971 war in the Jammu and Kashmir region, was to be respected by both sides and converted into the “Line of Control” (LoC).

Neither side would attempt to alter it unilaterally, regardless of mutual differences.

Normalization of Relations:

Both parties agreed to take steps to restore and normalize diplomatic relations, economic ties, communication links, and cultural exchanges.

Repatriation of Prisoners of War:

India agreed to release over 90,000 Pakistani prisoners of war captured during the 1971 conflict.

Withdrawal of Troops:

Troops were to be withdrawn to pre-war positions, with India agreeing to return captured territory in West Pakistan, as a gesture of goodwill.

Framework for Future Engagement:

The agreement called for a “step-by-step” approach towards solving bilateral issues, emphasizing patience and cooperation.

The Simla Agreement holds lasting importance for several reasons:

Bilateralism:

It set a fundamental principle that all disputes, including Kashmir, should be resolved bilaterally without external intervention — a clause India has repeatedly cited to counter Pakistan’s efforts to internationalize the Kashmir issue at the United Nations and other forums.

Strategic Stability:

By formally respecting the LoC and committing to peaceful resolution, the agreement aimed to reduce the chances of further wars and promote strategic stability.

Humanitarian Achievement:

The agreement facilitated the safe return of Pakistani POWs, an issue of immense domestic importance in Pakistan.

Foundation for Future Talks:

It provided a framework for future dialogue processes, such as the Lahore Declaration (1999) and subsequent peace initiatives.

Despite its historic nature, the Simla Agreement has also faced substantial criticism and challenges over the decades:

Pakistan’s Disillusionment: Many in Pakistan felt that the agreement disproportionately favored India, particularly by deferring the Kashmir issue to future negotiations without any firm deadline or international involvement.

Kargil Conflict (1999): The Pakistani infiltration across the LoC during the Kargil War was seen as a clear violation of the Simla Agreement, severely damaging trust between the two nations.

Bilateralism vs. Internationalization: While India insists that all matters must be addressed bilaterally, Pakistan continues to seek international mediation, arguing that bilateral negotiations have not made substantive progress, especially regarding Kashmir.

Ambiguity Over Kashmir: Critics argue that the Simla Agreement, by not explicitly resolving the Kashmir dispute and leaving it for future bilateral talks, created a lingering source of tension that continues to fuel hostility.

India continues to view the Simla Agreement as the cornerstone of its diplomatic position on Pakistan, emphasizing it even in the face of Pakistan’s international campaigns on Kashmir. After the abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution (which granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir) in 2019, India reiterated that the LoC must be respected as per the Simla framework.

Pakistan, however, argues that given alleged violations by India and a lack of meaningful dialogue, the spirit of the Simla Agreement has been undermined, thus justifying its appeals to the international community.

The Simla Agreement remains a crucial document in the complex and often tense relationship between India and Pakistan. It was a pragmatic and hopeful attempt to build a new relationship after one of the darkest chapters in their shared history. Although not without flaws, it demonstrated the potential for diplomacy and personal leadership in resolving deep-seated conflicts. Going forward, honoring the principles of the Simla Agreement — mutual respect, peaceful negotiation, and commitment to bilateralism — remains vital for any hope of lasting peace in South Asia.

With these two crucial and historic treaties thrown into the gauntlet, the future of South Asia remains uncertain at least in the near future.